I have reviewed thousands of technical drawings during my time in manufacturing. I have seen simple edge mistakes accidentally double the cost of a project, and I have seen supposedly perfect designs crack under pressure because they used the wrong finish.

You do not need a geometry lecture. You just need to know which edge to pick for your specific part.

In this guide, I will break down the real-world differences between Fillets and Chamfers. You will learn exactly how to save money on machining, keep your 3D prints from failing, and stop your parts from rusting. Let’s get to it.

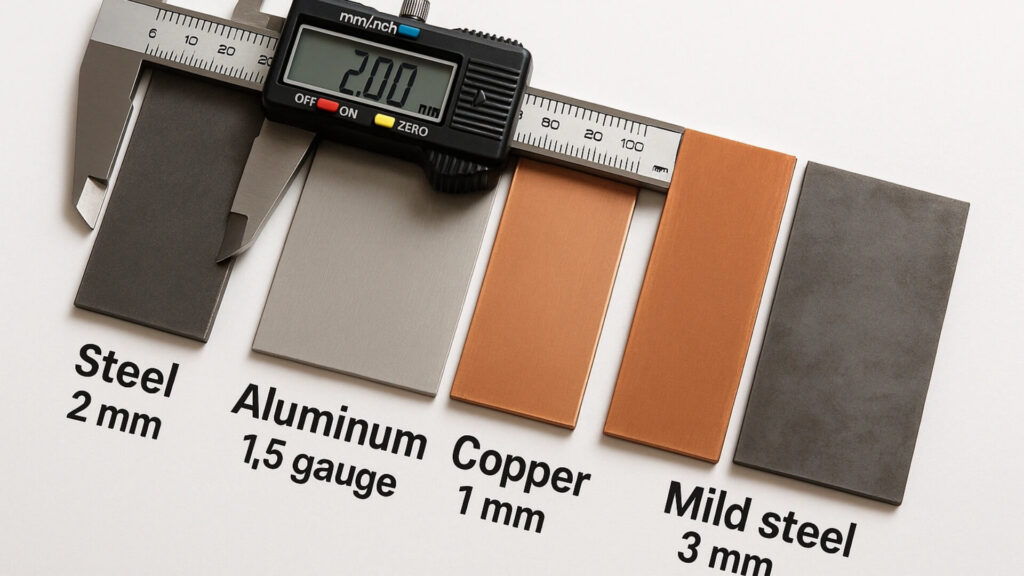

What is a Chamfer?

Think of a chamfer as a chopped-off corner. Instead of a sharp 90-degree edge, you slice the material flat to create a slope. It looks clean, modern, and industrial.

Distinguishing Features

The key feature of a chamfer is that it is flat. It does not curve.

Most machinery cuts chamfers at a 45-degree angle. This is the standard “default” in design because it removes the sharp point evenly from both sides of the corner.

The Main Benefits

Why do machinists love chamfers? Because they are easy and cheap.

- Fast Machining: Making a chamfer usually takes one single pass with a tool. It is quick work, which keeps your costs down.

- Easy Assembly: Have you ever struggled to force a bolt into a tight hole? A chamfer acts like a funnel. It guides the bolt (or mating part) right into place without jamming.

- Deburring: Freshly cut metal acts like a razor blade. This is particularly true for parts coming directly off our laser cutters. In our shop, we have seen operators slice through heavy-duty gloves simply by handling raw parts that skipped the chamfering stage. A quick mechanical chamfer knocks off those sharp burrs. It’s not just about design. It is about keeping the assembly team safe and avoiding blood on the final product

When to Use It

You should stick with chamfers if your main goal is speed or assembly. Use them for:

- Bolt Holes: To help screws slide in easily.

- Mass Production: If you are making 10,000 parts, the time saved on chamfering adds up to serious money.

- Internal Parts: If the part is hidden inside a machine and nobody sees it, use a chamfer. It functions perfectly and costs less.

Chamfers are great for saving time, but they aren’t perfect for everything. If your part needs to hold a lot of weight or look “soft” to the touch, you need a different approach.

What is a Fillet?

If a chamfer is a chop, a fillet is a blend. It creates a smooth, continuous curve between two surfaces. There are no sharp points here.

Distinguishing Features

The defining characteristic of a fillet is the radius. It isn’t an angle; it is an arc.

On an inside corner, a fillet creates a curved ramp (concave). On an outside edge, it rounds the corner off completely (convex), making it look like the edge of a phone case. The size of this curve is determined by the radius you choose in your design.

The Main Benefits

Fillets are the heavy lifters of the engineering world. They solve structural problems that chamfers simply can’t.

- Stops Cracks (Stress Reduction): Sharp inside corners are weak spots. This is a phenomenon known in mechanical engineering as stress concentration. Stress gathers at the sharp point and causes parts to snap. A fillet spreads that stress out over a larger area, making the part much stronger.

- Safer to Hold: Nobody wants to grab a sharp metal handle. Fillets smooth out edges so they feel ergonomic and safe in your hand.

- Better Flow: If you are designing pipes or molds for liquid plastic, sharp turns cause turbulence. Fillets allow air, water, or oil to flow smoothly around corners.

When to Use It

Fillets are usually necessary for the most critical parts of your project. You should use them for:

- Load-Bearing Parts: If the part holds heavy weight, like an engine bracket or a shelf support, you need fillets to prevent snapping.

- Handles and Tools: Anything a human hand touches frequently should be filleted for comfort.

- Premium Products: Rounded edges look finished and expensive. Apple products, for example, are covered in fillets.

Fillets make your parts stronger and prettier, but there is a catch. Creating those perfect curves often requires more effort than a simple flat cut. Let’s look at how that impacts your wallet.

Cost, Strength, and Speed Comparison

You know what they look like. Now, let’s talk about how they affect your budget and your part’s lifespan.

Cost and Machining Time

If you are on a tight budget, the chamfer is the winner.

Machinists can cut a chamfer in a single pass using a standard tool comfortably. It takes seconds. It’s fast, aggressive, and cheap.

Fillets are high maintenance. To make that perfect curve, a CNC machine often needs to make many tiny passes to blend the edge. Or, it requires a specialized tool called a ball nose mill.

- Chamfer: One quick swipe.

- Fillet: Slow, careful carving.

- Result: Fillets typically cost more machine time, which means they cost you more money.

Part Strength and Durability

If your part needs to hold a heavy load, the fillet takes the crown.

Imagine bending a stick. It always snaps at the weakest point. On a metal part, stress gathers in sharp inside corners. Even though a chamfer is angled, it still has edges where the angle starts and stops. These spots can crack under heavy weight or vibration.

A fillet solves this. The rounded shape spreads the stress out over a wider area. It eliminates the weak point almost entirely. If you are building a bracket for an engine or a crane, use a fillet.

The Vertical Wall Rule and Hidden Costs

Most online guides will tell you that fillets are always expensive. That is a dangerous generalization.

The real price depends on the orientation of the edge. You have to think about the shape of the cutting tool. It is a round, spinning cylinder.

- Vertical Corners (The Walls): When a round tool cuts into a corner, it naturally leaves a rounded shape. The machine literally cannot cut a sharp square corner inside a pocket. Therefore, a vertical fillet is effectively free. You are just letting the tool do its job.

- Horizontal Edges (The Floor): This is where the cost explodes. A standard tool has a flat bottom. It cuts a sharp, 90-degree angle where the wall meets the floor.

To get a rounded fillet on that bottom edge, the machinist has to stop everything. They must switch to a specialized ball end mill. Then, that tool has to trace the edge slowly, making tiny passes to carve the curve. It triples the machining time.

The Lesson: If you want a cheap, good-looking part, put fillets on your vertical walls, but keep your floor edges sharp.

Now that we have covered cutting metal, let’s look at a manufacturing method where the rules of gravity work completely differently.

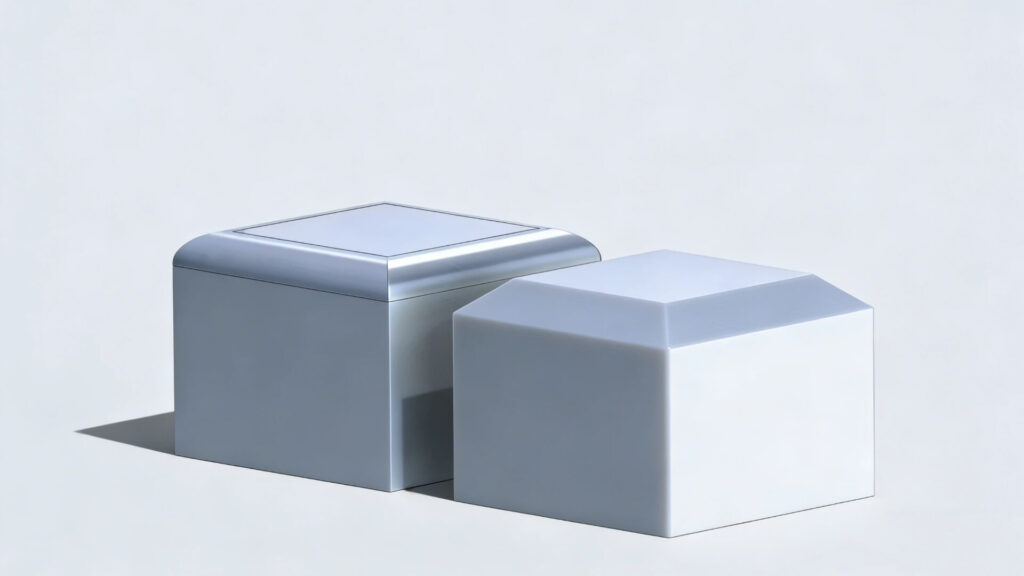

3D Printing: Why Chamfers Often Beat Fillets

Most design guides focus only on cutting metal. But if you are 3D printing your parts, the rules change completely.

You aren’t just cutting material away; you are fighting gravity.

The Overhang Problem

3D printers build parts layer by layer, from the bottom up. They cannot print on thin air. If an edge sticks out too far without support underneath, the hot plastic droops.

The Solution: Chamfers

A 45-degree chamfer is the magic angle for 3D printing.

It acts like a sturdy staircase. Each new layer uses the layer below it for support. You can print a chamfer perfectly without needing any messy “support material” to prop it up. It comes off the printer looking crisp and clean.

Why Fillets Fail

Fillets are rounded. This means the bottom of the curve starts horizontally—almost flat against the air.

When the printer tries to lay down those first few layers of the curve, there is nothing underneath to hold them. The plastic curls up and sags. The bottom of your beautiful rounded edge ends up looking like messy spaghetti.

Design Tip: If the edge is facing down toward the print bed, always use a chamfer.

Speaking of keeping your parts looking good, let’s look at one final hidden factor: rust.

Protective Finishes: Why Painters Prefer Fillets

If you plan to paint, powder coat, or anodize your parts, the edge you choose matters more than you think. It isn’t just about making it look nice. It is about stopping rust.

Liquid coatings hate sharp corners.

This is a phenomenon known as edge bleeding. When wet paint or powder hits a sharp peak (like the tip of a chamfer or a crisp 90-degree square), surface tension pulls the liquid away from the edge. It retreats.

- The Problem: This leaves the coating extremely thin—sometimes microscopic—right at the sharpest point.

- The Consequence: This weak spot is where moisture gets in. Our powder coating line supervisor refers to this specific defect as frame failure. We once had to reject a batch of 200 outdoor enclosures because the designer insisted on razor-sharp chamfered edges. After just 48 hours within a chamber running the ASTM B117 salt spray test, the rust began creeping in exactly where the sharp edge thinned out the paint.

Fillets are the solution.

Because a fillet is a smooth curve, the paint doesn’t pull away. It wraps continuously and evenly around the bend. You get a uniform thickness that seals the metal completely.

If your part will live outside in the rain or snow, use fillets. They extend the life of your paint job significantly.

We have covered a lot of technical ground. Let’s boil all of this down into a simple cheat sheet so you can make a decision right now.

Decision Cheat Sheet: Which One Do You Need?

We have covered the physics, the costs, and the manufacturing quirks. But sometimes you just need a quick answer.

Here is the breakdown at a glance.

Quick Comparison Table

| Scenario | Choose Chamfer | Choose Fillet |

|---|---|---|

| Budget & Speed | ✅ Best Choice. Fast, single-pass machining keeps costs low. | ❌ Slower. Often requires multiple passes or special ball-nose tools. |

| Heavy Loads | ❌ High stress concentration at corners; risk of cracking. | ✅ Best Choice. Distributes stress evenly; prevents structural failure. |

| Assembly (Bolts) | ✅ Acts as a perfect guide funnel for inserting screws. | ➖ No specific mechanical advantage for insertion. |

| Human Touch | ➖ Can feel “industrial” or sharp if not deburred perfectly. | ✅ Best Choice. Smooth, ergonomic, and feels premium/safe. |

| Powder Coating | ❌ High Risk. Sharp edges cause paint to thin out (edge bleeding) and rust. | ✅ Best Choice. Paint wraps continuously for a rust-proof seal. |

| 3D Printing | ✅ Safe. 45° angles are self-supporting and print cleanly. | ❌ Risk. Overhangs may droop or sag without support material. |

| CNC Vertical Walls | ❌ Impossible to cut sharp corners with round rotating tools. | ✅ Free. Naturally created by the round shape of the CNC end mill. |

⚠️ The Sheet Metal Exception (Must Read)

From a sheet metal fabrication perspective, fillets are not a choice—they are a necessity when bending.

I cannot tell you how many drawings land on my desk requesting a perfectly sharp 90-degree internal bend. It is physically impossible without cracking the material.

IIn our factory, every press brake tool has a natural radius (usually a small fillet). If you specify a sharp corner in your CAD file, but our tooling adds a 1mm fillet, it throws off your dimensional accuracy. Designing with this natural fillet in mind saves us hours of back-and-forth emails correcting your flat pattern.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use both on the same part?

Absolutely. It is actually smart design to mix them.

Most professional parts use a combination. Use fillets on the vertical inside corners to make the part strong. Then, use chamfers on the bolt holes and outside edges to save money. You get the strength where you need it and the savings where you don’t.

Is a 45-degree angle required for chamfers?

Not technically, but you should generally stick to it.

45 degrees is the industry standard. Most off-the-shelf cutting tools and drill bits come pre-made at this exact angle. If you ask for a specific 33-degree angle, the machinist might need to buy a custom tool or tilt the part in a complex way. That triggers extra fees.

Why is my machine shop charging me extra for fillets?

It comes down to time.

A chamfer tool cuts the edge in one fast, aggressive pass. To make a smooth fillet (especially on floor edges), the machine often has to make many tiny, slow passes with a special “ball-shaped” tool to blend the curve. In the machining world, time is money.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the choice between a fillet and a chamfer isn’t just a geometry lesson; it determines the lifecycle of your product. A chamfer might save you cents on machining time, but a fillet could save you thousands in warranty claims by preventing rust or stress fractures.

That is the perspective we take every day here at ShincoFab. As a China-based factory supporting manufacturing projects globally, we review thousands of CAD files every year. We often see designs that look perfect in software but would fail on the factory floor. Our goal isn’t just to cut what you send us, but to flag these small details—like suggesting a natural radius for a press brake part—before the metal ever hits the machine.

Whether you are prototyping a single bracket or scaling up for mass production, remember: the best edge is the one that balances cost with function. If you are ever in doubt, talk to your fabricator before you finalize your design.