Choosing the right grade of aluminum for your project is critical. To the untrained eye, every sheet of aluminum looks like the exact same piece of “silver metal.” But if you pick the wrong one, the consequences for your finished part can be expensive and irreversible.

Think about the trade-offs: an alloy engineered for aerospace might be incredibly strong, but it could deteriorate rapidly if you put it in a marine environment. On the flip side, an alloy that resists corrosion perfectly might not have the “muscles”—or yield strength—to handle the heavy loads needed for industrial machinery.

Every engineer wrestles with this decision. To clear up the confusion, we are going to break down the three most common aluminum families—5052, 6061, and 7075—so you can make your choice with confidence.

A Quick Overview of 5052, 6061, and 7075

Decoding the Numbers

Those four-digit codes on aluminum grades aren’t just random serial numbers. They follow a specific logic, and the key to cracking the code is looking at the first digit.

This number tells you the primary ingredient—or alloying element—mixed into the pure aluminum. That extra ingredient is what gives each series its specific “superpower.”

- 5xxx Series (e.g., 5052): Magnesium

The addition of magnesium creates an internal structure that is incredibly resistant to corrosion. This makes it the go-to choice for marine equipment that needs to survive constant exposure to saltwater. - 6xxx Series (e.g., 6061): Magnesium + Silicon

This combination allows the alloy to be heat-treated. It makes the metal versatile and easy to shape, which is why you often see this series extruded into complex structural frames. - 7xxx Series (e.g., 7075): Zinc

When you add zinc, you get a material that rivals the strength of steel. The advantage here is that you get that steel-like toughness while keeping the lightweight benefits of aluminum.

If the chemistry feels a bit heavy, here is a simple way to remember the basics:

- 5 (Magnesium) resists corrosion.

- 6 (Silicon) forms shapes.

- 7 (Zinc) builds strength.

How to Quickly Choose Between the Three Aluminum Alloys

If you don’t want to get bogged down in theory and just need a quick answer on whether to pick 5052, 6061, or 7075, this section is for you. Here is the fast track to making the right choice.

5052

- The Breakdown: This alloy is all about flexibility and ductility. If you need to bend, fold, or stamp the metal into shape without it cracking, 5052 is your first choice. For an alloy that cannot be heat-treated, it is surprisingly strong, and it handles saltwater corrosion exceptionally well.

- Best For: Sheet metal enclosures, marine fuel tanks, flooring, non-slip plates, and stamped parts.

6061

- The Breakdown: The structural all-rounder. It is reasonably priced, welds easily, has decent corrosion resistance, and provides good structural strength. If you walk into a machine shop and ask for “aluminum” without specifying a grade, they are likely handing you 6061. It is the default setting for general engineering.

- Best For: Structural framing, bicycle frames, architectural moldings, and general machined parts.

7075

- The Breakdown: This is the muscle. It offers strength comparable to steel, but it comes with trade-offs. It is expensive, extremely difficult to weld (often impossible for standard shops), and has lower corrosion resistance than the other two. You use this when you need steel-like strength but can’t afford the heavy weight.

- Best For: Aerospace gears, rock climbing equipment, competition bicycle components, and high-stress molds.

Summary

| Material | Key Ingredient | Traits | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5052 | Magnesium | Great flexibility; easy to bend; resists corrosion well. | Sheet metal, marine tanks, flooring, stamped parts. |

| 6061 | Magnesium + Silicon | Easy to weld; decent corrosion resistance; good structural strength. | Structural frames, bike frames, architecture, general parts. |

| 7075 | Zinc | High strength (rivals steel). | Aerospace gears, climbing gear, race bike parts, molds. |

How to Choose Based on Performance Properties

The cheat sheet above is just the basics. To really understand the specific performance differences between these three alloys—and how they handle real-world stress—we need to dig a little deeper. The following sections will give you the complete picture so you know exactly what you are working with.

Mechanical Properties & Strength (Static)

In the machining world, “strength” is a pretty vague term. To make a scientific choice, you need to evaluate two specific metrics: Tensile Strength and Yield Strength.

- Tensile Strength is the amount of load required to actually snap the material.

- Yield Strength is the amount of load required to permanently bend or deform it.

For most structural projects, Yield Strength is actually the most critical number. Think about it: once a part bends and won’t bounce back to its original shape, the structure has already failed, even if the metal didn’t snap in two.

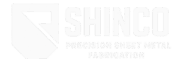

Before we compare the specific numbers, we need to address one major factor: Heat Treatment.

Aluminum’s performance depends heavily on its “temper.” The data below compares the industry standards you will typically find on the shelf: 5052 in its hardened state (H32), and 6061 and 7075 in their heat-treated state (T6).

Warning: Do not buy 7075 in an “O” (annealed) condition expecting high strength. Without that T6 heat treatment, 7075 loses its “muscle” status and becomes significantly softer and weaker.

The Strength Hierarchy

- 7075-T6 (The undisputed King): With a yield strength nearly double that of 6061, this alloy rivals many structural steels. It provides the highest strength-to-weight ratio of the three. If the part must withstand extreme fatigue or high stress (like an aircraft wing spar), this is the only option in this list.

- 6061-T6 (The Standard): It possesses “good” strength. It is sufficient for structural frames, walkways, and vehicle chassis. It is rigid, but under extreme loads where 7075 would hold firm, 6061 will deform.

- 5052-H32 (The Lowest): Strength is not this alloy’s primary feature. It has the lowest yield strength, meaning it bends easily—which is exactly what it is designed to do. High strength would make it brittle and prevent the forming characteristics it is prized for.

Hardness and Wear Resistance

Hardness is measured on the Brinell Scale. This number roughly dictates how the material resists surface dents and scratching.

- 7075 (High Brinell): Hard and brittle. It resists surface wear well, making it suitable for gears and shafts.

- 6061 (Medium Brinell): The middle ground. It is tough enough for structural parts and resists minor dings, but it isn’t as wear-resistant as 7075.

- 5052 (Low Brinell): Soft. It will scratch and dent easily in a machine shop environment.

Comparison Table: Strength & Hardness (Typical Values)

| Grade & Temper | Yield Strength (Point of Deformation) | Tensile Strength (Breaking Point) | Brinell Hardness | Elongation at Break (Formability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5052-H32 | 193 MPa (28,000 psi) | 228 MPa (33,000 psi) | 60 | 12% |

| 6061-T6 | 276 MPa (40,000 psi) | 310 MPa (45,000 psi) | 95 | 12-17% |

| 7075-T6 | 503 MPa (73,000 psi) | 572 MPa (83,000 psi) | 150 | 11% |

Note: Values represent typical industry averages. Specifics may vary slightly by manufacturer and sheet thickness. Source data referenced from MatWeb standards.

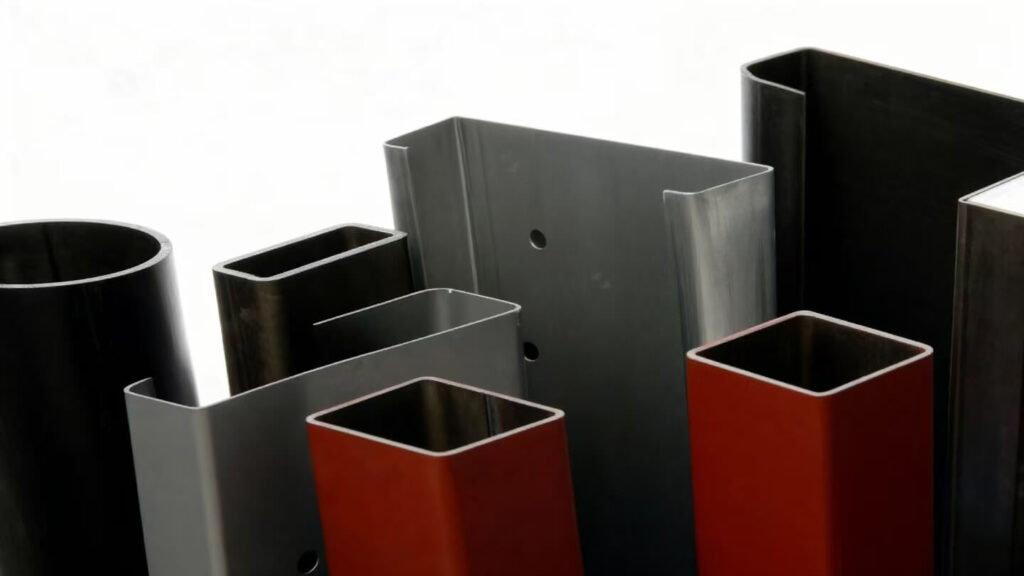

Formability & Bending (Sheet Metal)

Ask any press brake operator about their worst day, and they will likely tell you a story about a pallet of expensive alloy that cracked on every single bend.

On papers, “Formability” is a statistic. On the shop floor, it is the difference between a smooth 90-degree angle and a pile of scrap metal. When you apply tons of pressure to fold cold metal, the alloy’s internal structure dictates whether it flows or snaps.

The Breakdown

- 5052 (The Cold Forming Champion):

If your design requires complex bends, tight radii, or intricate stamping, this is the only logical choice. 5052 is famous for its workability. You can often bend it past 90 degrees or fold it back on itself (hemming) without a single micro-crack appearing on the surface. It stays where you put it and behaves predictably. - 6061 (The Risky Middle Ground):

Here is where fabricators get into trouble. 6061 is formable, BUT usually only in the annealed (O) or T4 temper. The vast majority of 6061 sold is T6 (heat treated for stiffness).- The T6 Problem: Because T6 is hardened, it resists bending. If you force 6061-T6 into a tight radius, the outer surface will stretch until it looks like “orange peel,” and then it will snap. You generally need a bend radius of at least 2x to 3x the material thickness to bend T6 safely.

- 7075 (The Nightmare):

Do not specify 7075 for sheet metal parts that require cold forming unless you enjoy frustration. Because of its massive yield strength, 7075 has incredible “spring back”—you might bend it to 90 degrees, and it will spring back to 80 degrees the moment the press releases. Furthermore, it is brittle; it usually snaps cleanly in two rather than taking a tight bend.

Pro-Tip: The “Anneal & Age” Workaround

If you absolutely need the structural rigidity of 6061 but the complex shape of a 5052 part, there is a hack—but it costs money.

- Buy 6061 in the “O” (Annealed) temper. It is soft and bends almost as easily as 5052.

- Form your part.

- Send the finished part to heat treatment to artificially age it back to T6.

warning: This adds significant lead time and cost, and can introduce warping.

Weldability & Joining

If your project requires joining parts via TIG or MIG welding, the material selection process changes drastically. Welding is not just about melting metal together; it is a mini-heat treatment process that alters the chemistry of the metal surrounding the joint.

This is where the concept of the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ) becomes critical. You might buy a sheet of aluminum with a specific strength, but the moment you strike an arc, the immense heat changes the temper of the metal adjacent to the weld.

The Breakdown

- 5052 ( The Welder’s Friend):

5052 is widely considered the best heavy-duty sheet aluminum for welding. Because it is hardened by cold-working (strain hardening) rather than heat treatment, the heat of welding does not degrade its strength as drastically as it does in the 6xxx series.- Filler Rod: Typically welded with 5356 filler rod.

- Result: Strong, consistent joints with high corrosion resistance.

- 6061 (The “Loss of Strength” Trap):

6061 is highly weldable—the bead lays down smoothly—but there is a structural catch that catches many engineers off guard.- The HAZ Drop: When you weld 6061-T6, the heat effectively “erases” the T6 temper in the Heat Affected Zone, reverting the metal near the weld back closer to its annealed (soft) state. You can lose up to 40-50% of the tensile strength right next to the weld.

- The Fix: Development engineers must account for this weakness in the design, or the entire welded assembly must be placed in a large oven for artificial aging to restore the T6 temper across the joint.

- Filler Rod: Commonly 4043 (easier flow) or 5356 (better color match for anodizing and higher strength).

- 7075 (The “Unweldable” Grade):

For general fabrication using standard TIG/MIG processes, 7075 is considered unweldable.- The Science: The chemistry that makes heavy zinc alloys so strong causes “hot cracking.” As the weld pool cools and solidifies, micro-cracks form almost instantly, compromising the joint’s integrity. While advanced aerospace techniques (like friction stir welding) can join it, you should never plan to weld 7075 in a standard shop environment. Join these parts using fasteners, bolts, or adhesives.

Honorable Mention: 6063 (For Aesthetics)

If your primary goal is not raw structural load-bearing but rather visual perfection, consider swapping 6061 for 6063.

- Why? 6061 welds are strong, but often have a different grain structure that shows up as a discoloration after anodizing. 6063 is engineered for architectural finishing; it welds easily and the zone blends seamlessly after anodizing, making it the top choice for visible frames and railing systems.

Machinability & Surface Finish

How a material behaves under a cutting tool determines the final cost and quality of your part. Machinability isn’t just about speed; it’s about the type of “chip” the metal produces and the surface finish it leaves behind.

The Machining Experience

- 7075 (The Machinist’s Dream):

Despite being hard, 7075 is widely loved by CNC operators. Because it is brittle, it breaks into tiny, crisp chips that fly away from the cutting tool. This prevents heat buildup and leaves a mirror-like finish right off the machine. You can run high feed rates and hold extremely tight tolerances. - 6061 (The Standard):

6061 machines well, but it is softer than 7075. It can be slightly “gummy,” meaning the chips might not break cleanly and can wrap around the tool (bird-nesting). It requires more attention to lubrication to ensure a smooth finish, but it generally poses no major issues. - 5052 (The Machinist’s Headache):

5052 is not designed for precision milling. It is soft and extremely gummy. Instead of cutting cleanly, the material tends to “smear” against the tool, leading to a rough, fuzzy surface finish. It creates long, stringy chips that clog machinery. Avoid milling 5052 if possible; stick to laser or waterjet cutting.

Anodizing & Aesthetics

If your part needs to look good (cosmetic finish), the alloy chemistry matters.

- 7075 (The Yellow Tint): Due to its high Zinc content, 7075 reacts differently to anodizing. Clear anodizing often results in a faint yellowish or gold tint rather than a pure silver look. It can also differ in color consistency compared to 6xxx series parts dyed in the same batch.

- 5052 (The Industrial Look): 5052 does not anodize well for cosmetic purposes. The grain structure often leads to a blotchy or muddy appearance. It is usually left raw or powder coated.

- 6061 (The Safe Bet): This is the standard for anodizing. It accepts dye well and produces consistent, vibrant colors (black, red, blue) or a clear, matte silver finish.

Corrosion Resistance

- 5052 (The Marine King): Unbeatable in saltwater or humid environments. It rarely requires protective plating.

- 6061 (The Middle Ground): Good corrosion resistance in normal atmospheric conditions, but will oxidize (turn white/chalky) over long periods outdoors without anodizing or paint.

- 7075 (The Weak Link): The high Zinc content makes 7075 susceptible to corrosion. It should generally not be used in corrosive environments without a strong protective coating (like hard anodizing).

Cost & Availability Analysis

When estimating a project budget, looking at the “price per pound” of the raw stock is a misleading metric. The true cost of a part is the sum of the material plus the time it takes to shape it. A cheap alloy that takes twice as long to machine is often more expensive than a premium alloy that cuts quickly.

Use this Relative Cost Index as a baseline for raw material pricing (assuming standard commodity shapes):

- 6061: 1x (The Baseline)

The standard reference price for the industry. - 5052: ~1x (Comparable)

Roughly the same price as 6061, though it fluctuates slightly depending on the shape you buy. - 7075: 2x to 3x (Premium)

Expect to pay double or triple the cost of 6061.

Material Cost vs. Labor Cost

The biggest economic pitfall for engineers is assuming that specifying the cheapest material yields the cheapest part. You must factor in Machinability.

1. The Hidden Cost of 5052 (The “Gummy” Factor)

You might save money on the raw stock of 5052, but if you require precision CNC machining, you will pay for it in labor. 5052 is soft and “gummy.” Instead of creating clean chips, it tends to smear and melt against the cutting tool.

- The Consequence: Machinists must run the machine slower (lower feed rates) and spend more time clearing clogged tools. Furthermore, achieving a smooth surface finish is difficult, often requiring secondary manual polishing.

- Verdict: Cheap to buy, expensive to machine.

2. The Efficiency of 7075 (The “Crisp” Factor)

7075 causes sticker shock when purchasing the raw block. However, it is an absolute dream to machine. It is hard and brittle, meaning it breaks into tiny, clean chips that fly off the cutter.

- The Consequence: Machines can run at high speeds with excellent tool life. A complex part might take 3 hours to machine in 5052 but only 1 hour in 7075.

- Verdict: Expensive to buy, but the reduced machine time can sometimes offset the material cost for complex parts.

3. The Balance of 6061

6061 remains the industry standard because it sits perfectly in the middle. It is affordable to buy and machines reliably well (“good enough” chips, decent speed). Unless you have a specific need for the formability of 5052 or the strength of 7075, 6061 usually offers the lowest Total Cost of Production.

How to Choose the Right Alloy for Your Application

You have seen the yield strengths, the cost indices, and the chemical compositions. Now, let’s translate that data into a final decision. Use this checklist to validate your selection before finalizing your Bill of Materials (BOM).

Choose 5052 If:

- You need to bend it: If the part is being made on a press brake or involves complex sheet metal folding (like an electronics chassis or enclosure), 5052 is mandatory to avoid cracking.

- It lives near saltwater: For boat hulls, marine hardware, or coastal infrastructure, 5052 offers the best corrosion protection of the group.

- It holds liquid: 5052 is the standard for fuel tanks and hydraulic reservoirs because of its high resistance to failure from vibration and its excellent weld integrity.

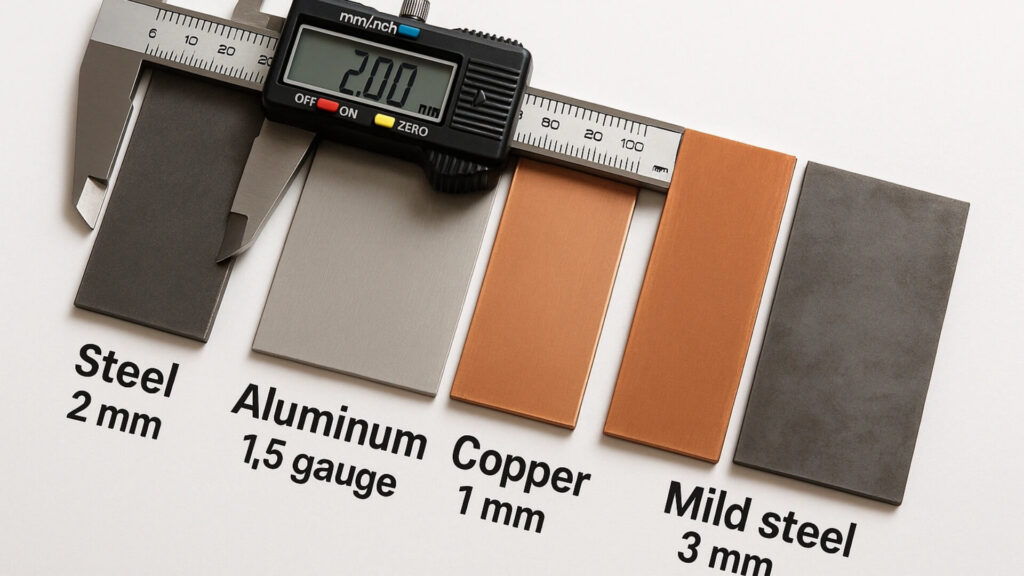

Choose 6061 If:

- You need a “Structural Skeleton”: For welded frames, trailer beds, car chassis, or automation gantries, 6061 is the industry default.

- You need T-Slot or Tubing: If your design relies on standard extruded shapes (angle iron, square tube, round pipe), 6061 is often the only choice available.

- Balance is key: You need a material that is reasonably strong, reasonably cheap, and easy to machine. It is the “Toyota Camry” of engineering materials—reliable in 90% of situations.

Choose 7075 If:

- Weight is the enemy: You are building drone arms, aircraft components, or competitive bicycle parts where every gram saved equals performance gained.

- Space is limited: You need the strength of steel but only have the physical space for an aluminum part (e.g., high-stress gears, rock climbing carabiners, or mold tools).

- Welding is NOT required: You plan to join the parts using bolts, screws, or adhesives.

When to Consider Alternatives

Sometimes the “Big Three” aren’t quite right. Here are two honorable mentions worth checking:

- Consider 2024 (The “Fatigue” Specialist): If you need the high strength of 7075 but are specifically worried about cyclic fatigue (e.g., an aircraft wing under constant tension/compression), 2024 is often the preferred aerospace choice. Note: It has poor corrosion resistance.

- Consider 6063 (The “Aesthetic” Specialist): If you are designing architectural trim, window frames, or consumer goods that require a flawless anodized finish, 6063 will look significantly better than 6061, which can turn “muddy” after anodizing.

Common Failure Scenarios (What happens if you choose wrong?)

Theory is one thing; the sound of expensive metal destroyed on the shop floor is another. If you ignore the specific properties of these alloys, you aren’t just risking a bad part—you are risking wasted weeks and thousands of dollars. Here is what failure looks like in the real world.

Scenario A: The Invisible Fracture (Welding 7075)

You need a high-strength bracket for a suspension system, so you choose 7075 because “stronger is better.” Your welder lays down a beautiful, stack-of-dimes TIG bead. Visually, it looks perfect.

The Reality: As the part cools, you hear a faint metallic ping. Then another. The chemistry of 7075 causes “zones of weakness” near the weld where the Zinc has migrated. You have induced hot cracking. These micro-cracks are often invisible to the naked eye. The part ships, is installed, and three weeks later, under a load that 6061 would have handled easily, the 7075 bracket snaps cleanly at the joint.

Scenario B: The Shop Floor Shrapnel (Bending 6061-T6)

You design a sheet metal enclosure with tight 90-degree flanges. You specify 6061-T6 because you want the box to be rigid and dent-resistant.

The Reality: The press brake operator lines up the sheet and engages the hydraulics. Instead of the metal flowing smoothly around the die, a violent crack echoes through the shop. The material didn’t bend; it sheared. Because 6061-T6 is artificially aged to be stiff, it has almost no elasticity for tight radius bending. You are left with two pieces of scrap metal and a terrified operator.

Scenario C: The “Gummy” Nightmare (Machining 5052)

You need a complex manifold with tight-tolerance holes for O-rings. You see that 5052 is cheaper than 6061, so you change the spec to save the client money.

The Reality: The machinist calls you in a rage. Every time the CNC cutter touches the block, the aluminum doesn’t chip away cleanly—it smears. 5052 is so soft and “gummy” that it melts onto the cutting tool (a phenomenon called “Built-Up Edge”). The resulting bore holes are oval-shaped and rugged instead of perfectly round and smooth. Attempts to sand it down just result in a cloudy, scratched mess. The part is functionally useless for sealing.

FAQ: Specialized Aluminum Questions

Q: Can you weld 7075 to 6061?

A: Practically speaking, no. While you can physically melt the two metals together using a 5356 or 4043 filler rod, the 7075 side of the joint is highly susceptible to “hot cracking” as it cools. The resulting weld will be brittle and structurally compromised. If you need to join a 7075 part to a 6061 frame, use mechanical fasteners (bolts or rivets) or industrial adhesives.

Q: Why can’t you bend 6061-T6?

A: The “T6” designation means the metal has been solution heat-treated and artificially aged. This process aligns the internal grain structure to maximize stiffness and rigidity. While this makes it excellent for structural frames, it destroys the material’s ductility (elongation). If you force 6061-T6 into a tight bend radius, the outer surface stretches beyond its limit and snaps.

Q: Is 7075 actually stronger than steel?

A: It depends on the type of steel. 7075-T6 has a yield strength of 73,000 psi, which is significantly higher than common structural mild steels like A36 (36,000 psi). However, high-strength alloy steels, such as 4140 Chromoly, are still stronger. The real advantage of 7075 lies in its strength-to-weight ratio—it provides the strength of mild steel while weighing only about one-third as much.

Q: What determines the price difference between these grades?

A: It comes down to ingredients and processing speed.

- Ingredients: 7075 contains higher amounts of Zinc and Copper, which are more expensive than the Magnesium and Silicon used in 5052/6061.

- Processing: 6061 is easy to extrude; it pushes through dies quickly. 7075 is hard and must be processed much slower to strictly control quality and prevent cracking during production. You are paying for the extra machine time at the mill.

Conclusion

There is no single “best” aluminum—only the best alloy for your specific application. Engineering is the art of balancing strength, workability, and budget.

- Choose 5052 if you need complex sheet metal bending, folding, or marine-grade corrosion resistance.

- Choose 6061 as your default structural workhorse for frames and general machine parts.

- Choose 7075 only when high strength and weight reduction are critical, and welding is not required.

Ready to manufacture?

At ShincoFab, we specialize in precision aluminum processing and sheet metal fabrication in China. Whether your project requires the flexibility of 5052 or the rigidity of 7075, our facility has the capabilities to turn your design into a finished product.

Upload your CAD files to ShincoFab today for a fast, competitive quote. Let our engineers review your specs to ensure you get the best performance for your budget.